Exploring the chameleon-like realm of tech industry taxation policies

Rewritten Article:

The Long Life of Digital Services Taxes: An Overview

Digital Services Taxes (DSTs) have become a hot topic in global taxation as countries rush to tap into the digital economy's revenue potential. Here's a lowdown on the current status of DSTs and their future prospects.

Just a week ago, Rachel Reeves was treading the geopolitical minefield that is Washington DC, trying to cut a deal with the US administration's top brass. Among the financial trophies adorning the walls of the Treasury, you might just find the UK's Digital Services Tax (DST) in due course. The US government has been flexing its muscles, laying down the law about European tax laws, and the UK’s DST is among their targets.

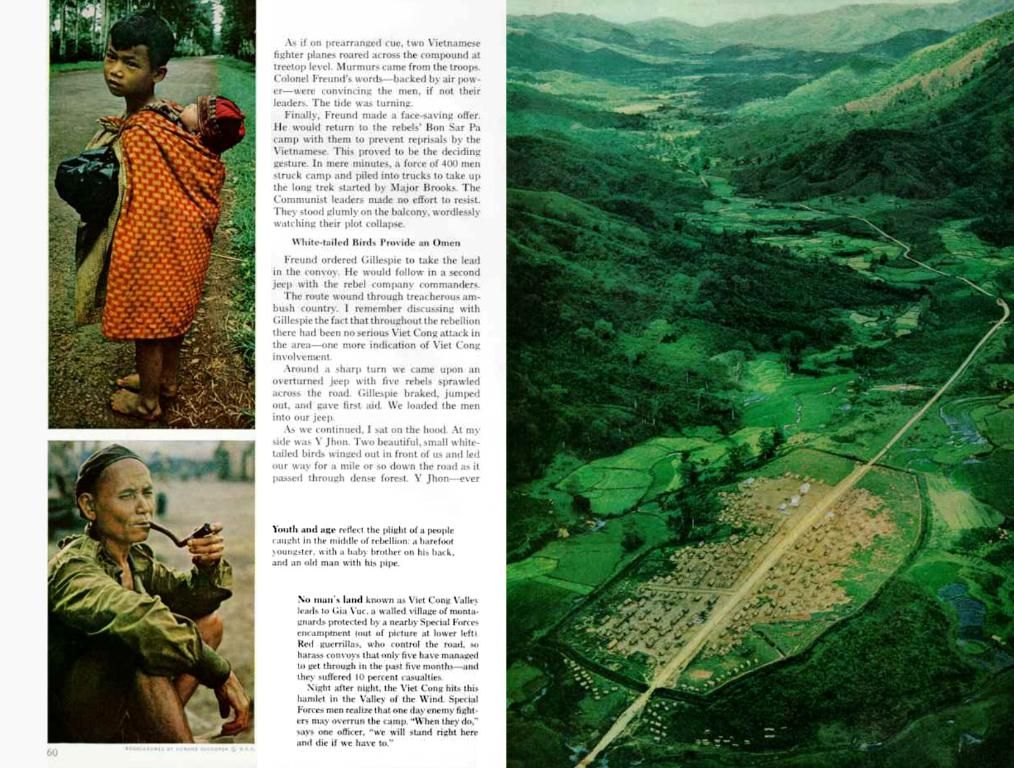

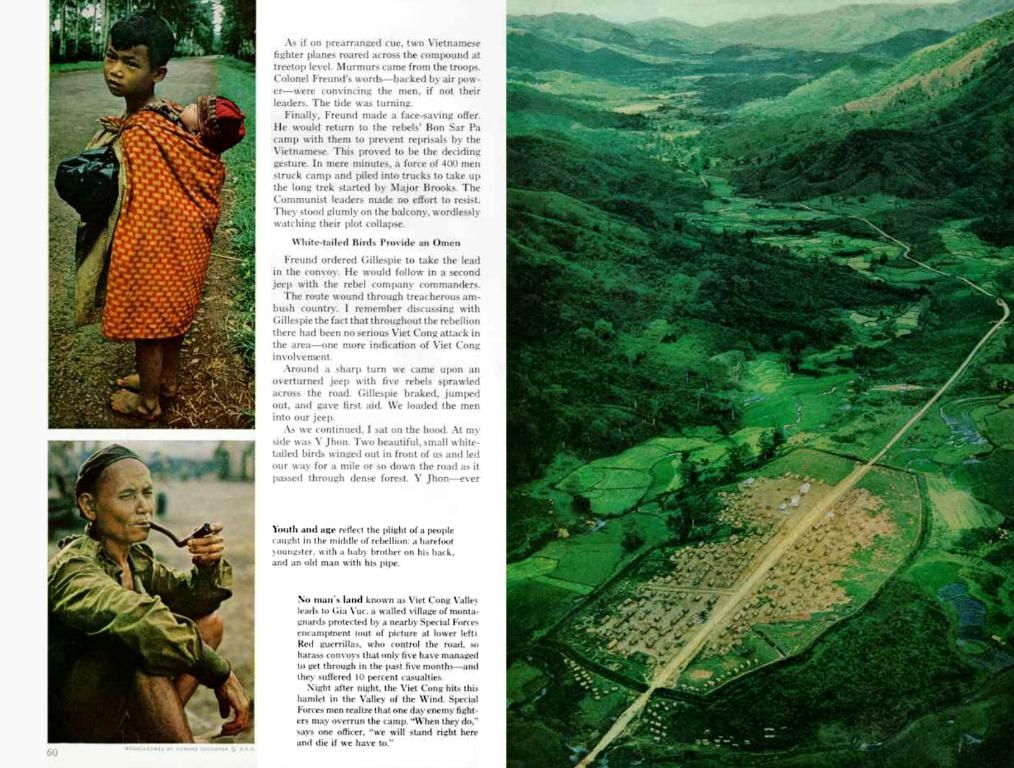

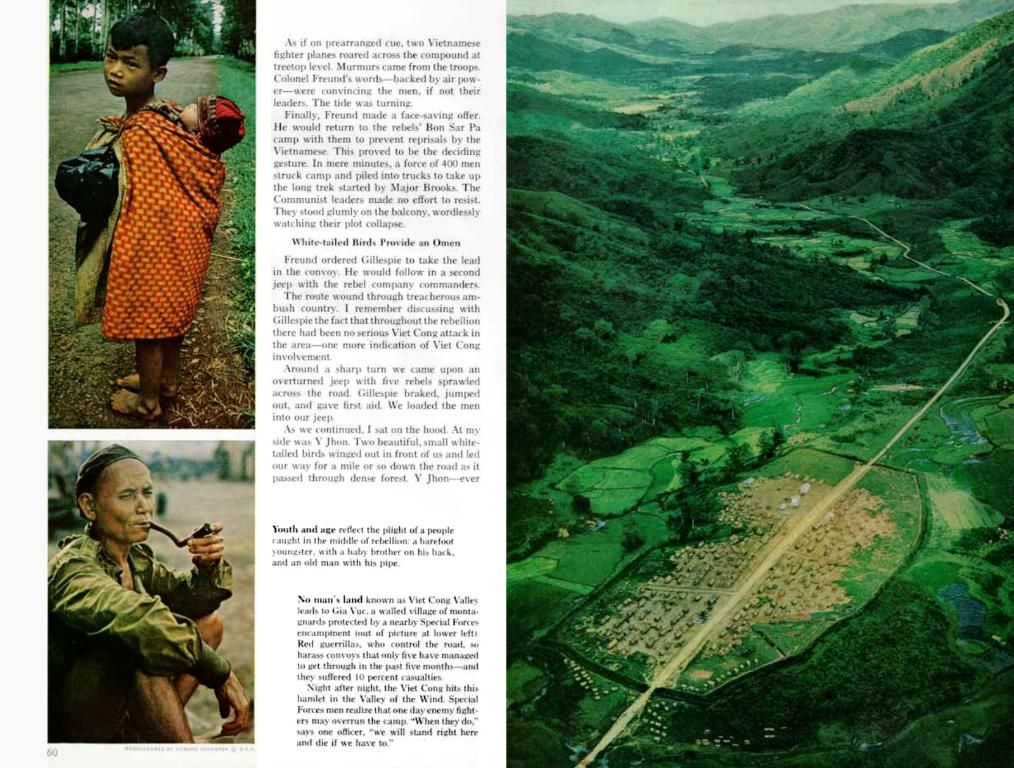

DST is a fairly selective tax, accounting for a small number of companies that actually pay it. Introduced by former Chancellor George Osborne in 2015, it's a percentage-based tax on UK digital revenues generated by the largest global social media platforms and online marketplaces. In 2023/24, it brought in just £670m for HM Treasury. Despite its minimal contribution, the British government remains attached to the DST, causing the ire of the Americans. But why does this seemingly insignificant tax attract so much attention?

DST is one of a flock of new taxes that have cropped up in the global fiscal regime since the dawn of the internet. They are what I'd call pay-to-play taxes, i.e., levies on tech giants for the privilege of servicing their desirable consumer market. Before the digital age, governments managed this with VAT, corporate income tax, and good old import tariffs.

The Internet's New Business Model

The internet's business model, where users receive services for free, while the platform earns money from advertisers, has thrown policy makers for a loop. It birthed the big idea that all the personal data consumers willingly give away for free has substantial value. Hence, data mining should come at a cost.

So now we have these DSTs. They're not just in Britain. Many countries are either considering introducing a DST or have threatened to do so if they don't get their preferred solution for market-based taxation, BEPS Pillar 1. However, due to the US's reluctance to participate in global tax agreements, such as the BEPS project, these types of taxes are likely to persist.

These types of taxes are shapeshifters, constantly evolving and difficult to pin down. What exactly are they? Not quite a corporation tax, nor a VAT, could they be a sin tax? In Uganda, the government imposed a 5% social media levy to "stop gossip" (repealed after widespread protests). Kenya follows suit with a DST and a digital excise tax. In Tanzania, the innovative "blogger license fee" targets not multinationals but homegrown influencers.

None of these taxes generate significant revenue. All of them are high-profile and divisive. They're shining in the limelight in 2025 as a part of the US-global trade issue. But I doubt they'll disappear anytime soon. Governments will continue to be tempted by the allure of tax fairness and their social responsibility to address social media issues, along with tightening fiscal budgets.

While folks might cheer at the idea of taxing tech giants, the cost of sales-based taxes ultimately impacts the consumer.

In its current form, I think DSTs are a bit problematic. They're based on an unrealistic idea of value creation and data, adding another layer of complexity to the system. For instance, they either burden everyone, stifling innovation, or become irrelevant due to their narrow application. However, I don't think even the current US and global trade tensions will curb the enthusiasm for digital levies. Instead, they'll adapt to look less like they're targeting US multinationals. I believe they're not as endangered a species as they might appear.

Author's Note: Tim Sarson is the head of tax policy at KPMG.

- In 2023, the UK's Digital Services Tax (DST) generated £670m for the HM Treasury, indicating a small contribution from this tax despite government interest and US opposition.

- The US, due to its reluctance to participate in global tax agreements such as the BEPS project, is likely to see digital taxes like the UK's DST continue.

- In discussions considering market-based taxation, many countries are contemplating digital taxes or have threatened to impose them, including Uganda with a social media levy, Kenya with a DST and digital excise tax, and Tanzania with a blogger license fee.

- Accounting expert Tim Sarson, head of tax policy at KPMG, believes that digital levies like DSTs, despite controversy and minimal revenue, are not as endangered as they might seem and will likely persist in the future.